It is almost impossible to escape music in our lives, whether you take part in a military march, hear a bird singing, or regularly listen to “American Top 40” with Ryan Seacrest. And, depending on what you’re listening to, it is ALSO nearly impossible to resist the movement frequently associated with music: dancing. Our dance abilities may range from someone who looks like a wet noodle on the dance floor to someone that’s a ballet virtuoso, and sometimes our fragile self-image may prevent us from dancing at all in social situations. Despite varying abilities and inclinations to dance, all human cultures exhibit some form of dance that pairs with music. This week, we’ll discuss why humans dance, different types of dances around the world, and some benefits to dancing. Put on those dancing shoes and get ready to boogie... only after you read the rest of this article, of course.

Humans and Dancing

For a time, researchers had thought that humans were the only species that could dance to an external rhythm. Sure, we see might see videos of dogs “dancing” on the internet, but cats and dogs and even chimps – one of the closest relatives to humans – are unable to move in time to music or an external beat for the most part. In contrast, music has actually been shown to improve timing, coordination, and rhythm in humans. One cockatoo named Snowball changed the idea that only humans danced to music when he was recorded moving in time to music of various beats, with videos published on YouTube starting in 2007.

This discovery of Snowball’s ability to dance to music opened a can of worms and led to further research looking for where humans’ ability to dance came from. While we still don’t have a single answer, there are a few leading ideas.

One theory is that the ability to dance to music stems from the ability to imitate sounds and speech. Humans are one of a few species (along with cockatoos like Snowball) that are credited with the ability to recreate movements or speech simply by seeing and/or hearing. This ability of imitation is tied to “mirror neurons”, which are activated both when you perform a movement and when you simply observe someone else performing the same movement. Another aspect of this idea is that the parts of the brain responsible for movement and vocal learning developed in close connection for species that are able to dance to music. Because of the close connection between movement and vocal learning as well as our ability to imitate, humans in particular can listen to music and move their bodies accordingly.

While the theory is plausible, another theory proposes that dance has simply emerged from a more basic use of rhythm for social functions, which is seen in many other animals. For example, mating swans will perform patterned movements in coordination with one another, which might be considered “dancing”. Even honeybees will do a patterned “waggle dance” to communicate to other bees when they find a food source. This theory seems to suggest that humans can perform rhythmic movements like other animals, and we simply use that internal sense of rhythm to move with music as a social function.

Still other ideas suggest that human dancing is developmentally different than “dancing” in other species. While human dancing seems very closely tied to music and sound, the Superb Lyrebird is a bird species that has been shown to sing and perform dances independently without much connection between the sounds and movements. Much of this depends on how we define “dancing”.

Regardless of how humans developed the ability to dance to music, it does serve multiple uses in a social setting. One study published in the journal Nature linked dance ability to ratings of attractiveness in Jamaican men, with better dancing being associated with being more physically attractive, or more having more physical symmetry. Additionally, dancing can be used to connect with others. Besides couples dancing together, a few studies have shown that simply tapping or walking in time with others creates a feeling of connection among those people. Line dance, anyone?

Finally, dance itself is basically a “universal language” among humans. One study involved a dancer portraying various emotions through classical Indian dance, and both American and Indian viewers were able to easily identify the intended emotions. Overall, we can see that dancing to music is closely related to human biology and culture.

Types of Dance

While it would be impossible to cover EVERY dance, I tried to touch on a variety of dances seen throughout the world. One thing that you might see in examining dances around the world is how dance and its cultural function varies throughout the cultures:

Eskista - This is a high-energy dance originating in Ethiopia which involves a great deal of rolling and bouncing the shoulders. Some say it was created to imitate the movements of a snake. The eskista is danced at weddings, holiday celebrations, and gatherings in general and accompanies music from instruments like the krar, washint, drums, and masinqo. Money is sometimes awarded to the best dancer.

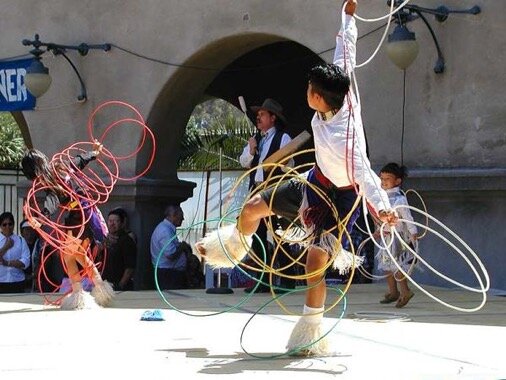

Personally, I can’t even hula hoop, so this is very impressive.

Hoop Dance: Originally a religious dance purported to have come from the Taos Pueblo tribe in the American southwest, the hoop dance is widespread among Native American peoples. The hoop is a sacred shape for many Native American tribes, and the hoop in the dance itself is used by the dancer to depict animals or tell stories. The modern-day version of the hoop dance is sometimes performed competitively and involves a solo dancer who uses a multitude of hoops in stylized fashion.

Hopak/Cossack: A traditional dance in Ukraine that involves a great deal of acrobatic squats, kicks, and leaping. This dance had originally been performed by young men looking to show off their skills, but is danced by both men and women in modern day to fast-paced orchestral music.

Sometimes Hopak dancers will yell “hop!” as they leap into the air, which contributed to the name of the dance.

Belly dancing: There are actually a number of different styles of the “belly dance” that have been around for thousands of years. The term Raqs baladi seems to classify the informal or social version of the dance and the term Raqs sharqi is used to more broadly characterize professional forms of the dance, although other terms are also thrown in at times. Sources trace the origins of the dance to areas of northern Africa (particularly Egypt), the Middle East, and India and also seem to depict the dance as traditionally performed by women to celebrate womanhood. Men have performed the dance historically as well, though.

Flamenco dancers showing off their moves.

Flamenco: A dance that originated in the region of Andalusia in southern Spain, with the original styles danced by gypsies according to some sources. The dance itself might involve stomping, clapping, and an array of arm movements that accompany singing and guitar. It is known for its emotional intensity, and the clothing associated with Flamenco dancers is very characteristic, often with brilliant colors.

Capoeira: An Afro-Brazilian style of dance, this one is also considered a martial art hybrid. It was derived from traditions of African people that had been enslaved and brought to the Portuguese colony of Brazil, where it was developed and practiced on plantations. The dance involves highly acrobatic movements such as spins and kicks that can also be used for fighting... and I’m not just talking about your average ol’ dance battle. It can be accompanied by an instrument such as the berimbau.

Why Dance?

So now we have some understanding of why humans started dancing and examples of dancing around the world, but what exactly does dancing do for us? There are actually a number of studies supporting the benefits of dance.

For one, it can be a nice workout. Dancing is considered a low-impact cardiovascular workout, so it serves as an alternative to running for those with bad knees or aching joints. A systematic literature review published in the Journal of Aging and Physical Activity stated that dancing can do the following for older adults:

Improve muscle endurance in the lower body

Improve flexibility, balance, and agility

Reduce the prevalence of falls

Reduce cardiovascular health risks

Improve bone-mineral content in the lower body

A different study from the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports found that elderly women in the study who frequently danced had a 73% lower chance of becoming disabled over the course of 8 years compared to the elderly women who did not dance. No other exercise in the study (which included calisthenics, walking, and yoga) had as strong of an association after adjusting for confounding factors. It’s important to consider how the TYPE of dancing affects physical outcomes, though, since some dances may require more coordination while others may require more stamina... and I’m not sure how many 80-year olds can perform Capoeira dance moves.

Zumba is one dance program that functions primarily as a cardio workout.

While physical benefits may be more obvious for dancing, mental benefits of dance are also well-studied. A 21-year study form the New England Journal of Medicine compared various activities for their effect on decreasing the rate of dementia. The activities in the study included reading, biking, swimming, playing golf, doing crossword puzzles at least 4 times per week, playing musical instruments, writing, walking, and dancing frequently (among a few other activities). The activity that provided the greatest reduction in risk for developing dementia was.... dancing frequently!

A general recommendation for improving mental capacity at any age is to exercise your cognitive processes through activities that require rapid-fire decision making as opposed to memorizing through repetition. Free-style social dancing can provide a great outlet for this improvisation and can also increase connectivity to others.

Dancing also seems to reduce the effects of certain mental conditions such as depression, low self-esteem, and tiredness. A study from 2013 published in JAMA Pediatrics tracked adolescent girls and the effects of a dance class intervention over the course of 20 months. The girls that participated in the dance intervention showed consistently higher self-rated health scores compared to a control group.

There’s still much to learn about the positive aspects of dance as an art form, a social pastime, and a healthy habit, but I should issue a warning that dance does have its limitations. In July 1518 A.D. in the European city of Strasbourg, a “dancing plague” was documented in historical records. This dancing plague caused hundreds of people to dance and move uncontrollably until some died of strokes or heart attacks...yikes. So while you’ve reached the end of this article and are now free to burn up the dance floor, just remember to dance responsibly.

To think about…

What do you define as “dancing”? Is music or rhythm necessary for dancing? As a cool aside, check out this article about individuals that are deaf and have exceled in professional dance: https://www.dancemagazine.com/deaf-dancers-2641619050.html?rebelltitem=1#rebelltitem1

What types of dance or dance moves do you see often see or experience on a regular basis? Where did these dances originate or how have they spread?

How can you potentially incorporate more dancing into your daily or weekly routine?

Sources

Sievers, et al. Music and movement share a dynamic structure that supports universal expressions of emotion, 17 December 2012. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (10.1073/pnas.1209023110)

Andrews. What was the dancing plague of 1518?, 25 March 2020. History Channel. (https://www.history.com/news/what-was-the-dancing-plague-of-1518)

Brown, Martinez, and Parsons. The Neural Basis of Human Dance, 12 October 2005. Cerebral Cortex. (https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhj057)

Pegasus. Your Brain on Music, ND. University of Central Florida. (https://www.ucf.edu/pegasus/your-brain-on-music/)

Monitor on Psychology. Why do we dance?, April 2010. American Psychological Association. (https://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/04/dance-research)

Dingfelder. Dance, dance evolution, April 2010. American Psychological Association. (https://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/04/dance)

Hogenboom. Where did the ability to dance come from?, 9 January 2017. BBC Earth. (http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20170106-where-did-the-ability-to-dance-come-from)

Weintraub. The dancing species: how moving together in time helps make us human, 4 June 2019. Aeon. (https://aeon.co/ideas/the-dancing-species-how-moving-together-in-time-helps-make-us-human)

Queensborough Community College. Dance Styles and History, ND. (https://qcc.libguides.com/c.php?g=818979&p=6267812)

Yamral Africa. Eskista: Ethiopian Dance, 9 February 2020. (https://www.yamralafrica.com/eskista-ethiopian-dance/)

Parks. The 16 Unique Ways People Dance All Over the World, 25 May 2020. Fodors Travel, (https://www.fodors.com/news/photos/the-16-unique-ways-people-dance-all-over-the-world)

Newell. What dance looks like in 20 countries around the world, 12 May 2020. Insider. (https://www.insider.com/20-dance-styles-from-around-the-world)

Dance Facts. Types of Dance – Categories, ND. (http://www.dancefacts.net/dance-types/types-of-dances/)

Weiser. Native American Dances, January 2020. Legends of America. (https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-dances/)

George. The Sacred Circle: Ostension in Native American Hoop Dancing, 2020. Utah State University. (https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2484&context=gradreports)

Iacono. History and Origins of Belly Dance, ND. World Belly Dance. (https://www.worldbellydance.com/history/)

Goncalves-Borrega. How Brazilian Capoeira Evolved From a Martial Art to an International Dance Craze, 21 September 2017. Smithsonian Magazine. (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/capoeira-occult-martial-art-international-dance-180964924/)

Ducharme. Dance Like Your Doctor Is Watching: It's Great for Your Mind and Body, 20 December 2018. Time. (https://time.com/5484237/dancing-health-benefits/)

Keogh, et al. Physical Benefits of Dancing for Healthy Older Adults: A Review, 2009. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. (https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.17.4.479)

Crees. Dancing and Cerebral Health, 2015. PIT Journal – University of North Carolina. (https://pitjournal.unc.edu/article/dancing-and-cerebral-health)

Powers. Use It or Lose It: Dancing Makes You Smarter, 30 July 2010. Stanford Dance. (http://www.joyfulboogie.com/uploads/2/1/6/1/21611390/dancing_makes_you_smarter.pdf)