Some studies estimate that up to 45% of the decisions we make on a daily basis are controlled by habits, with very little conscious thought or willpower involved. Trying to start up a new exercise routine as a New Years’ Resolution or attempting to break a reliance on coffee every morning can be more difficult than most of us would like to admit. Habits certainly aren’t all unhealthy or negative, though…. (hopefully) most people have established a habit of brushing their teeth every day or washing their hands after using the bathroom. Some companies may even rely on consumers “habit buying” their products in order to maintain a market share. Since habits seem to influence so much of what we do, this week we’ll take some time to go into more detail on where habits come from, the importance of habits, and some strategies for making and breaking our own habits. Maybe you can even use the strategies in this article to start a habit of reading each new Grow Weekly as it gets posted (which I will argue is a good habit)…

Where do Habits Come From?

First, it might be helpful to establish a definition of “habit”. Though it understandably varies, a habit can be loosely defined as a “response patterns that a person repeatedly exhibits in a specific situation” (Ersche, et al). Seems simple enough, but there are actually a number of concepts related to habit formation that are important to understanding where they come from. I’ll talk about a few of those concepts here:

Environmental cues: I’m not referring to the environment as in “nature”, but instead emphasizing the significance of “specific situation” in the definition above. Habits are considered to be responses to an external stimulus (or environmental cue), which is important so that you don’t suddenly decide to brush your teeth multiple times throughout the day (if brushing your teeth is a habit of yours). Instead, you might brush your teeth immediately after getting out of bed in the morning. In this case, the environmental cue might be the action of waking up which triggers your unconscious move to grab the toothbrush.

Environmental cues could almost be anything, from the cue of walking into the kitchen (and immediately opening the fridge to see what’s inside) to the cue of seeing a traffic light turn yellow while driving (and hitting the brakes… or the gas pedal depending on your philosophy of yellow lights). Some environmental cues can even be quite complex and involve a chain of cues and responses, which is probably typical of most people’s morning routines. Here’s an example of a chain of cues and responses…

NOT goal-oriented: In contrast to making conscious decisions, you don’t perform habits for any pre-meditated reason. This makes sense because I’m sure we all would rather not perform some bad habits (like constantly eating candy), and we try to form good habits with some difficulty (like eating healthy). Habits are basically automatic, so it doesn’t matter whether or not the habit matches with your goals or intentions… you’re still going to perform that habit under the right environmental cue. When you initially try to start a good habit, you may repeat the same action over and over and over again. The key is to consciously repeat this action enough under the right conditions so that your goal doesn’t even matter anymore… you just automatically carry out the good habit without the conscious intention of doing so.

One example of this characteristic of habits was seen in a study of moviegoers eating popcorn while at the movie theater. Experimenters gave frequent moviegoers popcorn that was stale (about a week old) during a movie, but they still ate the same amount as they usually did with fresh popcorn despite afterwards reporting that the popcorn was awful. This contrasted with a control group of moviegoers that did not frequently eat popcorn at the movies and ate significantly less of the stale popcorn. The habit of eating popcorn during a movie was so strong for frequent moviegoers that they ate the same amount of popcorn regardless of flavor or satisfaction.

Eating quick snacks like ice cream, popcorn, or chips while watching TV or a movie can become a pretty strong habit. Eventually you may find it hard to eat something without watching TV because of that habit… and vice versa.

Willpower and Stress: As much as we might like to think that changing our habits is easy, it requires a great deal of willpower, which happens to be a limited resource. People that are more stressed, distracted, or rushed will be more likely to fall back into a habit as opposed to a calm and relaxed person that is more able to make goal-based decisions. So, for example, going grocery shopping during a stressful weekday may lead you to buy the same old things as opposed to shopping on a calmer weekend when you have more cognitive capacity to make decisions based on health or budget goals.

Similarly, exerting self-control takes a toll, and trying to complete too many activities in one day that require self-control can actually deplete you and make you revert back to habits unwillingly. We have a limited amount of willpower. One study actually tested smokers who were either told to resist eating a plate of sweet treats or told to resist eating a plate of less-tempting vegetables with a subsequent 10-minute break following the temptation. The smokers that had to resist the sweet treats were significantly more likely to smoke during the 10-minute break than those that had to resist the vegetables. So, we can assume that greater self-control used to resist a greater temptation (sweet treats) left those smokers with less self-control to curb their smoking habit. Basically, trying to form too many good habits or break too many bad habits at the same time may be too much for our limited willpower.

Smoking presents an interesting situation because even though it can be considered a psychological “habit”, it also has chemically addictive nicotine

Habits are created by repetition over time in a stable context and grow stronger over time or with more repetition. Initially, we probably have a goal in mind, even if that goal is as trivial as: I need to get ready for work in the morning. Doing the same morning routine every weekday with the same pattern of events and the same ol’ route to work will eventually result in a habit due to an extremely stable context and a whole lot of repetition over time. Eventually, you may even find that you did something without realizing it, such as locking the front door and then second-guessing whether you actually did because you initially did it unconsciously as part of your habit. The same process of habit formation applies to other habits that you may or may not be aware of.

The Importance of Habits (harmful and helpful)

In general, habits are very helpful to us as humans since they help free up our attention for other activities. For example, when someone learns how to drive a car, they might require a significant amount of focus to keep the car between the lines and at a stable speed while also navigating to the correct location. Fast forward a few years, and that same driver performs those same functions while holding a full conversation, drinking coffee, and listening to the radio. Driving at this point has become a habit with its own set of complex environmental cues and responses. Here it can be a bit dangerous, though, since driving still requires conscious focus to respond to unexpected events, such as the animal that just jumped in front of your car. Besides the general cognitive benefits of habit formation, habits play a pretty important role in our everyday lives.

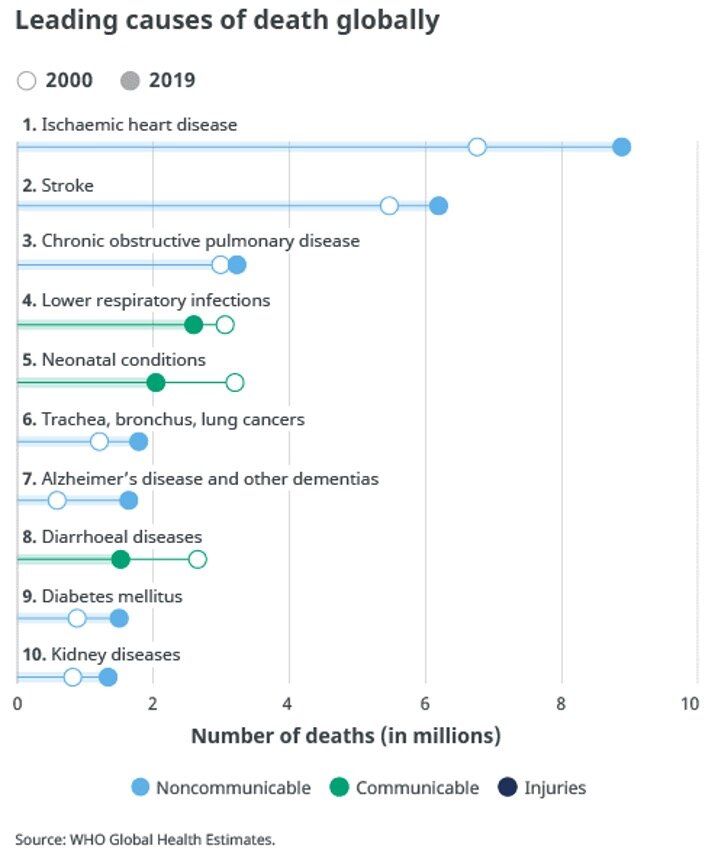

One of the major areas where habits are routinely discussed is the realm of health. Diet, exercise, hygiene, drug/substance use… the list goes on. Habits are particularly relevant here because long-term patterns of behavior (e.g., eating a balanced diet regularly for years) typically have a much more significant effect on health than a one-time event (e.g., I ate a whole leaf of lettuce today). Consider the list of the leading causes of death worldwide shown in the adjacent image.

Many of these causes of death are preventable through lifestyle choices that may be governed by habits. Obesity caused by unhealthy diet habits and a lack of physical activity can increase the risk for heart diseases (#1 cause of death), cerebrovascular diseases (such as #2 cause of death), lower respiratory diseases (such as #3 cause of death), and even some cancers (#6 cause of death). A habit of smoking can also increase the risk for many of these causes of death. The absence of a good habit can also be detrimental, such as forgetting to take your medication… AGAIN. Making a habit of taking prescription medication regularly as prescribed can ensure that you stick to the schedule even when you’re stressed or have depleted self-control (and are then more likely to fall back onto habits, whether good or bad). A simple habit that can help to prevent transmission of infectious diseases is washing your hands after using the bathroom, which is ~hopefully~ a strong habit by this point.

Besides health, where else do habits become important? Well, some businesses rely on consumer habits to generate ca$h money. One way that businesses do this is through the idea of habit buying. The action of habit buying typically only occurs with cheaper products that are regularly purchased, like toilet paper or laundry detergent. In this case, you typically purchase the same brand and product over and over again (e.g., Charmin Ultra Strong toilet paper with the cute bear on it) until it becomes subconscious simply due to the fact that you’re not dissatisfied with the product.

The Charmin bears are obsessed with their toilet paper, so they exhibit brand loyalty – NOT habit buying!

You might be stressed or rushed and simply grab the same product off the shelf subconsciously based on past experience – this is habit buying. An example can be found with purchasing milk regularly. If you’re rushed, you may instinctively grab a gallon of milk at the store even though you already have one at home and most certainly did not need the extra gallon. Habit buying is also different from brand loyalty since I’m sure a good portion of us are not overly enthusiastic about the brand of toilet paper or toothpaste that we use.

Certain types of targeted marketing try to take advantage of consumer habits in ways that are similar to habit buying. Customers can be attracted through rewards programs or regular sales that are conducive to forming habits. Then, once the customer forms the habit of going to that store, the sale or reward isn’t even needed to attract the customer. For example, stores like Target may try to attract pregnant women in particular through marketing and offering special coupons. Since pregnancy is usually outside of the normal routine, the pregnant woman is willing to shop at Target as a new customer and deviate from their usual shopping patterns. After some time, the pregnant woman establishes a new habit of regularly going to Target for all her shopping needs – even potentially after they have the baby.

In the end, you do save brain power through habit buying by not having to think about all of your options for various retailers, brands, and products… but you could also be missing out on a hot deal.

Strategies to Make and Break Habits

So now we know a little bit about habits and that they’re important for health, business, and freeing up cognitive function. But how do we exert influence over our habits by making good ones and breaking bad ones? Thankfully, there’s PLENTY of advice out there. Here are some tips and tricks that seem to be most helpful (and somewhat backed by research!)

Breaking habits: identify and remove the environmental cue! This is certainly easier said than done, but changing up your environment will also shake up your habits. At moments when you have more time and space to make conscious or deliberative decisions (as opposed to the automatic habits), make the choice to avoid a certain environmental cue in the first place. This could take the form of literally moving the furniture in your room… if your couch is in a different location, it may cause you to think twice about plopping down to watch TV. This idea extends to people that change jobs, move to a new area, establish a new set of friends, or just generally have a major life event. At these turning points, environmental cues typically change and no longer trigger habits as easily, allowing you to break free from those old habits.

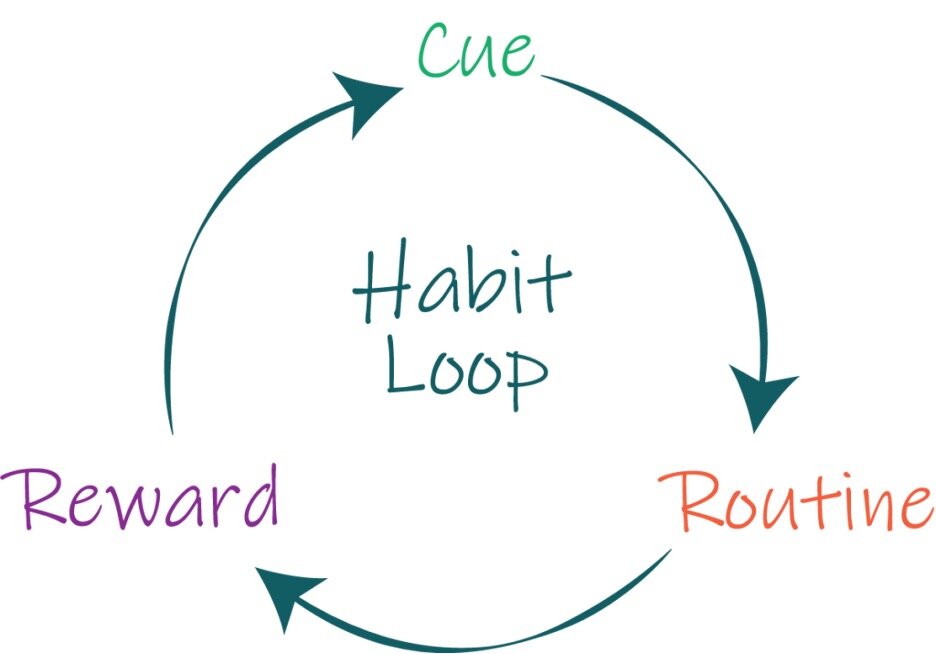

Making habits: establish a reward program… in a particular way. Having some form of reward to motivate you is a useful way to achieve goal-oriented behavior, which is not habitual. This goal-oriented behavior is usually not sustainable in the long-term because the reward might be limited (there’s only so much money in the world) or you may decide the reward isn’t worth it when things get stressful. One way to address this is to create an “interval schedule” for rewards. Instead of rewarding yourself every single time that you perform the desired action (e.g., eating dessert every day after going to the gym), establish an intermittent and delayed schedule for giving yourself the reward only after performing the desired action consistently (e.g., buy yourself a nice chocolate cake at the end of the week if you went to the gym each day). This action of an interval schedule helps to separate the reward from your desired action, which helps your brain develop a habit without the need for the reward every single time. This habit formation still takes time, so even slowly reducing the intermittent reward over time until it’s gone completely might be a strategy to use.

The Reward helps start this loop, but you may try to eventually remove the Reward… and have the Cue and Routine remain as a subconscious habit.

Breaking habits: be less stressed. HA! Nice one. But seriously though, stress often makes us fall back on our old habits (as discussed earlier in this article). Finding ways to relax and de-stress, especially in situations and during times that we typically perform the undesired habit, will help you maintain awareness and avoid falling back into the habit you’re trying to break.

Screenshot from a habit-tracking app called “Habitica” that turns habits into a game of sorts.

Timely reminders. This goes for both making and breaking habits. Using technology can actually help here, since there are plenty of reminder and calendar apps that can help alert you when you want to perform a certain habit (e.g., have an alarm go off for when you planned to go on a run) or catch your attention before you continue an old undesired habit (e.g., set a warning message alert for when you normally take a smoke break). Similar to these apps and technological alerts are things called “point-of-choice prompts” which take the form of reminders in locations where a decision is made. For example, having a sticky note message on the lid of your trash can might remind you to recycle if it’s a possible alternative. These point-of-choice prompts lose their luster over time since they slowly become part of the normal routine and environmental cue, but hopefully the initial prompting is enough to help change a habit for the better.

Making habits: start small and make it easy to begin. Instead of saying, “I’m going to study for 2 hours every day,” try to start smaller and work your way up. The key is consistency in a stable context, so you could alter your goal to be studying for just 30 minutes in the library at the same time each day. Over time, maybe you can lengthen that time to reach 2 hours, but starting with a major time or energy commitment from scratch can sometimes wear down your conscious willpower and prevent the commitment from becoming a continuous, steady habit.

Making habits: there’s no set time that it takes to establish a habit. No, it doesn’t seem to take 21 days or 30 days to make a habit or whatever other magic number that seems to get thrown around. A study from the European Journal of Social Psychology in 2009 investigated habit formation and found that it took participants anywhere from 18 to 254 days to approach complete automatic habitual behavior for given daily habits related to eating, drinking, and physical activity. That’s a pretty wide range. The researchers of the same study also stated that missing one day of the desired habit did not significantly affect formation of the habit, so that’s consoling.

And as always, stay motivated until you make or break the habit (I’m not sure if this is backed by any study, but it sounds nice)! As this article comes to a close, it can be interesting to reflect on how much of our lives seems to be lived on “auto-pilot” through habits. It’s certainly not a bad thing in my opinion since habits can be extraordinarily powerful… if you figure out how to control them. Just think of professional athletes or musicians that have habits of practicing their skill every day. When all is said and done, maybe being called a “creature of habit” is a compliment?

To think about…

Reflect on some of the habits that you might have in your daily life. What do you think are the environmental cues that trigger those habits?

Which habits might you want to change in your life, and how do those habits affect your health, finances, social interactions, and overall goals?

What types of rewards might motivate you to start a habit, and what strategies do you think would work best for you to make or break a habit?

Sources

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5473478/

https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/the-science-and-theory-of-habit-formation/

https://www.kpa.io/blog/making-safety-a-habit

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1559827618818044

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6545a1.htm

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

https://marketbusinessnews.com/financial-glossary/habit-buying/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1057740807700372

https://productcoalition.com/how-to-create-habit-forming-shopping-experience-a0b1e026fb86

https://www.npr.org/2012/03/05/147192599/habits-how-they-form-and-how-to-break-them

https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/changing-habits/

Roberto & Kawachi. Behavioral Economics & Public Health, 2016. Oxford University Press.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-wise/201904/the-science-habits

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/11/career-lab-habits

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1509/jppm.25.1.90

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/are-habits-more-powerful-than-decisions-marketers-hope-so/